You are currently logged-out. You can log-in or create an account to see more talks, save favorites, and more. more info

The Meeting of American Culture and Buddhism

AI Suggested Keywords:

Lecture Series

The talk explores the intersection of Zen practice and poetry, focusing on the concept of enlightenment articulated in Zen teachings and how these principles inform the speaker's work as a poet. A key story discussed involves Baso and Nangaku, which illustrates the Zen teaching that true understanding comes from being fully oneself, akin to the idea that true poetry arises from an authentic voice. The speaker also discusses the anthology "Women in Praise of the Sacred," highlighting women's contributions to spiritual poetry across various traditions, while examining the challenges of language and categorization.

- "Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind" by Shunryu Suzuki: The story of Baso and Nangaku from this book demonstrates the importance of understanding one’s own nature in Zen and poetry.

- Works of Dogen Zenji: Provides a commentary on the story of Baso and Nangaku, reinforcing the notion of authentic self-realization in Zen practice and poetry.

- "Women in Praise of the Sacred" (Anthology): An anthology curated by the speaker, showcasing poetry by women from diverse spiritual traditions, emphasizing themes of awakening and spiritual expression.

- Gnostic Gospel of Thomas: Mentioned in relation to the idea of the kingdom of heaven being present on Earth, parallel to Zen concepts of inherent enlightenment.

- Tricycle Magazine: Cited in the context of deep ecology and the holistic view of all things as interconnected within Buddhist philosophy.

- "The Elements of Chemistry" by Antoine Lavoisier: His principle that nothing is lost, nothing is created, everything is transformed, ties to themes of change and impermanence in Zen practice.

- Theragatha (Buddhist Texts): Refers to the songs and experiences of early Buddhist nuns, illustrating historical women’s voices in spiritual practice.

- Poetry from Asian traditions: References to influences from Asian poets and no-drama plays underline the integration of Zen ideas in Western poetic forms.

- Native American and Aztec poetry: Highlighted as part of a stream of thought concerning transience and impermanence, resonating with Zen teachings.

AI Suggested Title: Awakening Through Poetic Zen Voices

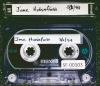

Side A:

Speaker: Jane Hirshfield

Possible Title: The Meeting of Buddhism and American Culture Lecture Series

Location: SF Zen Center City Center

Additional text:

Side B:

Speaker: Jane Hirshfield

Possible Title: The Meeting of Buddhism and American Culture Lecture Series

Location: SF Zen Center City Center

Additional text:

@AI-Vision_v003

I never did full lotus, half lily, I was a specialist in half lily and still am to this day. Well, when I think about Zen and myself as a poet and the connection between them, what comes to mind first for some reason is the story which I first met in Zen Mind Beginner's Mind of Nangako and Baso and the tile, which I'm sure most of you know, but in case anybody doesn't I will briefly repeat. One day Baso, who was a strong young Zen student who was nicknamed the Horse Master, which I of course like a lot because I like horses a good deal, he was sitting Zazen and his teacher out in the garden and his teacher Nangako came by and said to him, what are you doing?

[01:12]

And Baso answered, I'm trying to become a Buddha, and Nangako said, ah, and went on his way. And a few minutes later, when Baso got up, Nangako was sitting down in another part of the garden with a tile and a cloth, rubbing and rubbing and rubbing very vigorously. And Baso said to his teacher, what are you doing? And Nangako said, I'm trying to make a jeweled mirror out of this tile. And Baso said, you can't make a jeweled mirror out of a tile by rubbing it. And the reply was, you think you can make a Buddha by sitting meditation? And when Suzuki Roshi tells this story, he also gives Dogen Zenji's commentary on it from the 13th century. Dogen says, when the horse master becomes the horse master, Zen becomes Zen.

[02:13]

That's, for me, the connection between poetry and practice, that when things become completely themselves, they are Zen. Poetry, for me, is a path towards awakening in language. I'm not a Zen poet the way one thinks of Zen poets as being. Last month, when Diane talked in this series, she gave a very wonderful description about how Zen came into the arts in America in the 1950s and the 1960s, the aesthetics of spontaneity and allowing chance into your work and presenting the moment as you found it. Alan Ginsberg's saying, first thought, best thought, none of that applies to me, I'm afraid. I don't fit the description of a Zen poet.

[03:17]

So, I have to find some other excuse besides the fact that I can say two things. One is, I can say that I'm not a Zen poet, I'm a poet who has practiced Zen since 1974, so maybe that lets me off the hook a bit. As all labels are kind of difficult for me, none of us, I think, is very comfortable even saying, I'm a poet, or even saying, I'm a Buddhist. Nobody really likes to say, I'm a Buddhist. You might be able to say, with a bit more comfort, I sit, I write, verbs. Verbs are much more comfortable than nouns. And one thing which, I mean, for me, this whole question of categories and language has been quite acute over the last two years because one of the projects I've been working on in addition to my own poetry is this anthology called Women in Praise of the Sacred, which

[04:22]

draws on all traditions in which I've basically looked for poetry which I found awake and alive and that lifted my heart and that made me feel more deeply human from every tradition by women. There have been a lot of books about women's spirituality in the last 15 years and none of them has been only the words of women describing their own experience. They tend to be ... and again, it's a question of the fuzziness of language. When you talk about feminine, the feminine and the spiritual, most of these books are about female images of the sacred or the divine or whatever, be it the goddess Inanna or even one could say the Buddhist moon, which I like very much.

[05:24]

I like the Buddhist moon because of course it's quite genderless, it's without gender, but still this sort of hackneyed cliche is that the sun is the male image and the moon is the female image, so one could say that the moon is a figure for enlightenment, it's a sort of feminine image. But I wasn't looking for feminine images, I was looking for what women say about their experience and what I found was that there were women in every tradition whose words could be found that I didn't know about, starting with the world's earliest identified author who was a Sumerian moon priestess in 2300 BCE named Enheduanna, who we have a portrait of. She's quite a historical figure. She's a woman who got caught in political conflicts in the Middle East, got caught between warring sides, right through the 12th century Daoist women teachers who Thomas Cleary brought

[06:27]

into English for the first time, so that was how I found out about them, Rabia, a Sufi woman in the 8th century who lived in Basra, a town familiar to us from the Gulf War. Women in Northern Europe in the 12th through 14th centuries who make a marvelous example for something I've been very interested in. One of the reasons that I was drawn to Zen Center and Zen practice was because you could be a lay person and still have monastic experience, which for me was an amazing opportunity, for me to be able to live at Tassajara fully and completely and accepted as an equal there, but still be a lay person, you know, not sign on to the Western idea of what it means to become a monastic. That was a tremendously important part of my life and remains at the center of my life.

[07:29]

Well, women in Northern Europe in the 12th through 14th century, there was a movement called the Beguines where the church stopped opening new convents and women who really, there was an imbalance of population between the plague and the Crusades, men were dying, there were a lot of extra women, the church didn't want to take care of them, so they said no more convents, but the women who really wanted to practice wouldn't be stopped. And so they began by meeting together in one another's homes five times a day for shared prayer and by the apex of the movement in the 13th and 14th century, you could find cities with 14,000 women living together within the walls, practicing voluntary poverty, chastity and good works. They did a lot of hospice work. They took care of people, they took care of each other, and this was all done as laypeople.

[08:31]

There was no institutional support whatsoever from the church. They simply made up the forms for themselves and they weren't held by lifetime vows. They could come and go if they wished. You could do it for a while and then if you wanted to go marry, that was all right. And that kind of flexibility, which I recognize from my experience in this community, to find that that had existed to that extent in the Western tradition was an amazement to me. But all of this is a long circle. I was talking about language and categories and the difficulty, and here I have created a book with the title that I myself am somewhat uncomfortable with, Women in Praise of the Sacred. I've already fallen into a problem by the time I say even the word sacred, because my own feeling is that the horse master becoming the horse master has nothing to do with the

[09:33]

sacred. It has nothing to do with an idea of something other than ourselves. And yet, in putting together this book, there was no language where I could both communicate what I wanted to communicate to someone who might see a title on a bookshelf and pick it up that would also remain true to my own sense of things. And so the only solution for me was to give up my own sense of things to some extent and to merely present these various other realities always in their own terms, to take on their language and allow them to speak. And I was simply the person who was lucky enough to get to do the project, and it was good fortune to get to do it, I think. So that's something about language. Another thing about language, to come back to poetry and Zen and me, is that of course

[10:36]

poetry is an ultimate case of endeavoring to practice right speech. It makes you question what right speech might be, because in trying to make a poem that works, that wonderful word we use in poetry workshops, it works, we say, everything in it has to be right speech. If you have lied or hesitated or fooled yourself or lost your awareness or lost your concentration, the speech won't be right and the poem will stumble. So this is another way that my sense of practice and my sense of poetry coincide. I think that for me they've always been terribly linked because I found out about Buddhist ideas through poetry. I know most people of my generation first encountered Zen through listening to Alan

[11:38]

Watts or something like that, Gary Snyder, Alan Ginsberg. I didn't. I first met Buddhist ideas in no-drama plays and in Chinese classical poets. And I also met the ideas of Zen not even in the tradition of Buddhism, which is something that I was thinking about in terms of the title of this whole series, not the Zen and the Arts title, which is this year's theme, but the big title, which is The Meeting of Buddhism and American Culture. And it seems to me that long before Zen or Buddhism or Dharma or any of those words was ever named in this country, in this culture, still the ideas of Buddhism have always been a part of who we are because the ideas of Buddhism don't come from Buddhism.

[12:40]

They come from the truth of our experience. They come from paying attention to the nature of our own lives. And so the concept of everything changing, of transience, I first met that reading the Roman poets, probably, Horace and Catullus, talking about carpe diem, seize the day because the day will quickly pass. A theme which has run through English poetry, has run through Western poetry. There's even something that I can't claim influenced me particularly before coming here, but there's a wonderful stream of poetry in Native American poetry, in the ancient Aztec poems of the 15th century. There is a series of poems which talk about the transience of the flowers and that talk about how our life is here but for a moment.

[13:44]

Who can say that our life on this earth is real? And the poems, you could lift some lines of them and put them into Japanese or Chinese poetry and you wouldn't know which tradition they had come from. So I don't think that American culture is devoid of the ideas of awakening, of transience, of interconnection before Buddhism comes into it. Those ideas are about the way the world is and so those ideas were always here. And I know when I first was attracted to Zen and Buddhism from finding the description of them in poems, in Asian poetry, it wasn't a matter of seeing something new. It was a matter of recognizing a description of the world that I already agreed with, that confirmed my sense of ah, this I understand, this I agree with.

[14:49]

So why then, if it's already completely present and if we already think we understand it, why come spend eight years as a full-time Zen student? And of course, that again is Dogen's question, if we're all already Buddha, why practice? And I guess for me there were two reasons. One was I knew I needed help. It's one thing to have a moment's insight or understanding or some experience, which I think many people have in their childhood or teenage years, some taste of what Buddhist practice then leads us back to, but we don't know how to integrate it into our lives. And there could have been another path perhaps, but this is the only one which made sense to me. This made a lot of sense to come and sit and examine and question everything for a long time until I got some sense of how to do it into my body, into my mind.

[15:55]

And only then did I feel like I could go back to poetry. And it never even crossed my mind to go to a writing graduate school. Fewer people did it back then than do now. Now almost everyone does, but I knew that if I wanted to write, which I did want to do, I had always wanted to write, I felt as if the only way to do that was not to go to a school and read books and fall in and out of love again, which was the only real experience I knew was book experience and falling in love, but it was to look more closely at what it means to live in this world. And so I sometimes, when I'm talking to poetry students, say that Tassajara was my graduate school. I didn't get any degree, but that's where I chose to go to graduate school. What I'd like to do for the rest of my time here is, I don't know how many of you came

[17:01]

because you have an interest in the anthology. Michael had directed me when I asked him, you know, what do you want me to do with this evening? He said, please concentrate on your own work, not the anthology. So what I'll do is I'll read you some poems from the new book, which I feel, even though I hardly ever use the language of Buddhism in my poems, I'll have one poem that I'll read you that actually tells a Buddhist story in it, and it tells a lot of I feel like they have a close relationship to practice. And then after that we can have a question and answer, and if people want to hear some of the poems from the anthology, I've flagged a bunch of the early Buddhist poems and I can read you some of those or whatever, or we can talk about anything you want together. But first I'll read you some of these. And this is sort of enjoyable for me.

[18:03]

I've just begun giving readings from these books. I've only had copies of them for a couple of weeks, and what's nice about reading in this context is I get to read different poems in a different way than what I've been doing in bookstores, so it's a privilege for me to be able to give them to you. For example, with this poem I can tell you what is not said anywhere in the poem, but which you will all recognize, which is it's a poem which comes out of Zazen experience. The Door. A note waterfalls steadily through us, just below hearing. Or this early light, streaming through dusty glass. What enters, enters like that, unstoppable gift. And yet there is also the other, the breath space held between any call and its answer.

[19:04]

In the querying first scuff of footstep, the wood owls repeating, the two counting heart. A little Sabbath, minnow whose brightness silvers past time. The rest note, unwritten, hinged between worlds, that precedes change and allows it. So it's a poem about the fact that if you don't let emptiness in, form can't become form, truly. The space between our breathing, as important as counting our breathing. The gap, the place where nothing is, being just as important as the space where something is. This next poem, I was thinking for a long time, one of my favorite sayings is a saying by Gensha, quoted by Dogen.

[20:06]

All the world is one bright pearl. There's also in every mystical tradition, every tradition where people see for themselves, you find some variation of this idea. In the Gnostic gospel of Thomas, it's phrased as, the kingdom of heaven is already here on earth, only men do not see. The idea of the perfection of things as they are, the idea that you're already Buddha. You may not realize it, but you're already Buddha. And thinking about that is what this poem came from. Each step. Nowhere on this earth is it not a place where the lovers turn lightly in sleep in each other's arms. The blue pastures of dusk flowing gladly into the dawn. Nowhere that is not reached by the scent of good bread through an open window. By the flash of fish in the flashing of summer streams, or the trees unfolding their praises, apricots, pears, of the winter chill nights.

[21:16]

Briefly, briefly we see it and forget. As if the spell were too powerful to hold on the tongue, as if we preferred the weight to the prize. Like a horse that carries on his own back the sacks of oats he will need, unsuspecting, looking always ahead, over the mountains, to where sweet springs lie. He remembers this much from his youth, the taste of things, cold and pure. While the water sound sings on and on, unlistened to, in his ears. While each step is nothing less than the glistening river body re-entering home. The House in Winter Here, in the year's late tide wash, a corner cupboard suddenly wavers in low-flung sunlight, cupboard never quite visible before.

[22:27]

Its jars of last summer's peaches have come into their native gold. Not the sweetness of last summer, but today's, fresh from the tree of winter. The mouth swallows peach and says gold. Though they dazzle and are gone, the halves of fruit, the winter light, the cupboard it has swept back into shadow. As inhaled, swiftly or slowly, the sweet wood scent goes out the same. Saying, not world, but the bright self breathing. Saying, not self, but the world's bright breath. Saying, finally, always, gone, the deep shelves of the heartbeat empty. Or perhaps it is that the house only constructs itself while we look. Opens room from room because we look.

[23:31]

The wood, the glass, the linen, flinging themselves into form at the clap of our footsteps. As the hard dormant peach tree wades into blossom and leaf at the spring sun's knock. Neither surprised nor expectant, but every cell awakened at that knock. When I was saying that the ideas of Buddhism are found everywhere already in the culture, one of the places that interested me was a chemist who I met reminded me about Lavoisier, the guy who is considered the father of modern chemistry. And he was telling the story and he said the sentence which Lavoisier came up with

[24:33]

in order to talk about the law of the conservation of matter. And what struck me is it's a perfect embodiment of Buddhist teaching. What he said was, so this is in 1789, the year of the French Revolution, in his radical textbook, Elements of Chemistry, he said, nothing is lost, nothing created, everything is transformed. The experiment with which he proved this was one in which he took mercuric oxide and separated it into mercury and oxygen, weighed them separately, weighed them recombined, and it never changed. And that's how he knew that oxygen too was matter and had weight and substance and all of that. And that comes up later in the poem. So it was a poem in which I was trying to bring a little more peace with myself

[25:34]

to the creations of modern chemistry, to the technological world. I was thinking about Lavoisier and what he made for us all and what it has come to and what did I have to think about that. I don't know if any of you read Tricycle. There was a wonderful section in the last issue about deep ecology in which one of the writers suggested that you can't take belching smokestacks and nuclear warheads and diesel trucks and say everything is Buddha except them. And if everything is Buddha, everything is Buddha. Which doesn't mean you don't then try to get rid of the nuclear warheads, but to remember to include them in the perfection of things as they are. The Wedding. The high windows stream with fish, the gold luck of carp, the tiny silver luck of minnows,

[26:39]

while the earth gives back her buried wealth of skunks and star-crossed badgers. Pure stripes of seeing unfurl themselves out of moonlight, and the dark bodies follow as closely as boat follows sail, and know no harm will come to them in their wholeness. All beings rise, uncaught, for this beginning. Cousin Death joins a table at the wedding, the white cloth gleams, the waiting plates, all are made welcome. Mother War smooths the silk of her dress, she feels young, and will dance again, after years, with her husband, Pity. Still the guests are arriving, carrying gifts, small appliances, vases, a thick set of towels, lamps of heaviest brass. They say each other's names, charity, hope, and ask of nieces and nephews off to school.

[27:47]

A rabbit edges near, outside the glass. On the river a barge floats softly, its tugs at slack, night herons and pelicans preen, an iron bell warms with the slow ringing fire of rust, and the barge imperceptibly lowers. Imagine, nothing created, what it might look like. Try to envision such peace. Now, see the dark-shelled flowers of thought unmade, the petals of little boy unassembled, the plague-poxed donkeys unflung over city walls, the dead undead, the survivors unlonely. Or think of a world in which nothing is lost, its heaped paintings, the studded statues keeping their jewels. Now see this very world, where all is transformed, quick as a child who cries and then laughs in her crying,

[28:51]

now ingot, now blossoming ash, now table, now suckling lamb on that table. How each thing meets the other as itself, the luminous changing mirror of itself, mercuric oxide tipped from flask to flask, first two, then one, wedded for life in that vow. This is a rather different story, which also has a Zen thing stuck into Western culture. Anybody know the official name for this? Thank you. An Enso, a calligraphy circle, which crops up in a story told by Vasari in the lives of the artists. I think I'll tip you off. Sometimes poems are meant to be read twice,

[29:53]

but they only get to be heard once. So what's being described in the beginning of this, I was looking at an art book, which had pictures of the Giotto Chapel. So it's Giotto. A Plenitude. Even from a book of aging plates, these frescoes' intricate traceries dazzle the eye with their crazed China, 14th century glaze. In gold walls, gold vines flicker and rise in intertwining diamonds. In red bedding, damask blooms. Each swath of floor or cloth, a plenitude that binds. Each peak-roofed canopy, a worked geometry of laddered tiles or stones whose almost symmetry is repetition as in nature, invented, always new. For these storied rooms seem not so much built up by plan as breathed. Until at times they seem to break

[30:56]

as if from sheer exuberance to daplings spilled out selfless as animal pelts or roots whose autumn pattern nets a hill against the rain's entreating beat to join in falling. Other times, though, they seem delicately revealed, as if some smooth and outer rind had been peeled back to show the web of sweet-celled seed-on-seed that is the world. But there is the story, too, of a young painter meeting the envoy of a pope. Asked for a work by which his art could be weighed against others, he dipped his stylus, with great courtesy, according to Vasari, in red ink and drew a single, perfect O. Shocked, the messenger asked, will this be all? Young Giotto, whose deerfly his teacher

[31:58]

had tried in vain to brush from a painting, replied, it is enough and more. I think I'm going to introduce one not explicitly practiced poem, but because I have a friend here from the well. This is a poem which came out of a different kind of interconnection, the Indra's net of the internet. During the Gulf War, I was put on the well, which is a computer bulletin board based in Sausalito, two days before the beginning of the war. And I followed the war on the well, which was an amazing news source because people were posting not only a huge range of their own ideas and responses and reactions, and a huge range of factual information because of the different backgrounds

[32:58]

of people on there, but also they were importing in information that was being posted elsewhere on the internet. One of the most interesting things was a diary being kept by an Israeli writer named Robert Werman, giving his day-by-day experience of waiting for the bombs to come in. And that got turned into a book which has just been published. I meant to note the name of it, it just finally came out. But he would say, okay, they've just put off the sirens, excuse me a minute, and then he would take his computer and move into the sealed room with the nine members of his family who were there that night because it was the Sabbath and then he would continue and one day he happened to mention in passing that the Narcissus had just begun to bloom in Tel Aviv. And I looked out my window

[33:59]

and my Narcissus had just begun to bloom. And I realized that everywhere the Narcissus had just begun to bloom. And so that became this. Narcissus, Tel Aviv, Baghdad, San Francisco, February 1991. And then the precise opening everywhere of the flowers which live, after all, in their own time. It seemed they were oblivious but they were not. They included it all, the nameless explosions and the oil fires in every cell, the white petals like mirrors opening in a slow motion coming apart, and the stems, the stems rising like green flaring missiles, like smoke, like the small sounds shaken from those who were beaten, like dust from a carpet into the wind and the spring-scented rain.

[35:00]

They opened because it was time and they had no choice. As the children were born in that time and that place and became what they would perhaps for the lucky, the foolish or brave. But precise and in fact wholly peaceful the flowers opened and precise and peaceful the earth opened because it was asked. Again and again it was asked and earth opened, flowered and fell because what was falling had asked and could not be refused as the seabirds that asked the green surface to open are not refused but are instantly welcomed that they may enter and eat as soon refuse battered and soaking the dark mahogany rain. One of the things

[36:11]

I've been practicing with in the last few years is a question what is the emotional life of a Buddha? And I have a theory about this which may be leading me and all who listen to hell realms. I don't know. I could be very, very wrong but I think the emotional life of a Buddha is a very full emotional life. I realized that just as I have preconceptions about what I'm supposed to be as a Zen poet that I'm not. I had preconceptions about what I was supposed to be as a Buddhist that I'm not. And I began to look at them and realized that and I really am I'm not fooling when I say I could be really wrong about this. This could be a disaster but I realized that I had the image of the serene Buddha sitting on the lotus with the half-smile

[37:12]

of detachment in my mind as the only possible way and that everything else was some mistake departing from that. And I didn't even, you know, until the moment when I went, ah, I didn't even realize how strong this idea had been in me in all of my years of practice that that was right and that anything else was some failure or some falling away. And of course there are models in the tradition that don't say this but that was somewhere deep in my mind. And I began to think maybe not so. Maybe not. Maybe a Buddha looks just like we do. Maybe a Buddha laughs and cries and rages. And there is some difference because a Buddha has an interest. That would be the difference. Not on her or his or its own behalf

[38:13]

but simply because this is the life of the world. Certainly it's the life of the human realm that we're practicing in. And so that's something I've been thinking about a great deal and this is a poem which speaks about that a bit and oddly enough it speaks about it through a Western story rather than an Eastern one. Happiness. I think it was from the animals that St. Francis learned it is possible to cast yourself on the earth's good mercy and live. From the wolf who cast off the deep fierceness of her first heart and crept into the circle of sunlight in full weariness and wolf hunger wagging her newly shy tail and was fed and lived. From the birds who came fearless to him until he had no choice but return that courage. Even the least amoeba

[39:17]

touched on all sides by the opulent other. Even the baleened plankton fully immersed for what else might happiness be than to be porous opened rinsed through by the beings and things. Nor could he forget those other companions the shifting, ethereal, shapeless hopelessness desperateness loneliness even the fire-tongued anger for they too waited with the patient lion the drowsy mule to step out of the tree's protection and come in. I think it has to do maybe with the difference between detachment and non-attachment that I used to think we had to be detached and now I think

[40:17]

non-attachment will suffice and that the Buddha would rather have a full life although the other is good too. I don't mean to say it's not good to have the other but there are many possibilities. This is a poem about writing and it comes from a day there's a place I go in upstate New York which I think of as my writing Tassajara it's called Yaddo it's an artist's colony and I've gone five times now and I treat it very much as a retreat I spend a lot of time in silence there I don't go to the communal breakfast they give you a lunch in a bucket that you can take away to the writing room that they give you and so I spend the whole day without speaking to anybody else and I make a fire in the wood stove and I sit Zazen and I have all the time in the world and I talk and I meet

[41:25]

the other people there at night which is also wonderful and that is the one time when I ask myself to write every day I'm not a person for whom it works well to keep a daily writing schedule I believe that all of the people who suggest that one keep a daily writing schedule if one wants to be a writer they're right I can't do it my muse just doesn't cooperate but at Yaddo she cooperates so that's where I've got the pact one new thing every day and this is pretty much the accurate tale of the day when I didn't have an idea at all nothing came to me so it's a kind of pep talk that I gave myself towards the end of the day except for one thing

[42:25]

I changed those of you who know your Chinese stories will know the story actually is that the monk became enlightened when the little pebble he was sweeping hit a bamboo but I didn't have enough syllables in the line for bamboo so my poem says stone on stone and I love it because it has lots of internal rhyme in it and very good advice to boot it makes a reference to a poem called the Thought Fox by the English poet Ted Hughes and it quotes a Zen master with a quote that I bet a lot of you have heard and then the last line I wrote myself so this is called Inspiration while sweeping up of stone on stone

[43:27]

it's Emily's wisdom truth in circuit lies or see Grant's Common Birds and How to Know Them New York, Scriveners, 1901 the approach must be by detour advantage taken of rock, tree, mound and brush stealth's appearance watchfulness look guileless a loiterer, purposeless stroll on not too directly toward the bird avoiding any gaze too steadfast or failing still in this give voice to sundry whistles chirp, your quarry may stay on to answer more briefly try but stymied give it up do something else leave the untrappable thought go walking ideas buzz the air like flies return to work

[44:27]

a fox trots by not Hughes's sharp stinking thought fox but quite real outside the window with cream dipped tail and red fire legs doused watery brown emerges from the woods briefly squats not fox but vixen then moves along and out of sight enlightenment wrote one master is an accident though certain efforts make you accident prone the rest slants fox-like in and out of stones Percolation

[45:28]

In this rain that keeps us inside the frog wisest of creatures to whom all things come is happy rasping out of himself the tuneless anthem of frog further off and more like ourselves the cows are raising a huddling protest a ragtag crowd that can't get its chanting in time now the crickets seeming to welcome the early come twilight come in of all orchestras the most plaintive still in this rain soft as fog that can only be known the bottom is happy soaked to the bone sopped at the root fenny seeped through yielding as coffee grounds yield to their percolation blushing completely seduced

[46:31]

assenting as they give in to the downrushing water the murmur of falling the fluvial purling wash of all the ways matter loves matter riding its gravity down rising through cell strands of xylem leaflet and lung flower back into air now I'll just read one more poem and then we can talk or if you want you can hear some stuff from the anthology this is a short poem within this tree another tree inhabits the same body a November

[47:38]

yeah, ok let's hear more hear more, ok other people. There is no other world. This is it. It's all you get. Yeah? I'm curious that you personally, were you writing before you started practicing Saiphan? Yeah. I've written since I got taught how to write. I wrote steadily throughout my whole childhood and always thought that I would simply continue doing that, and then when I realized that I didn't know what it meant to be a human being and that you can't write if you don't know what it means to be a human being, that's when I came to Zen Center and I stopped writing. When I don't know what people say now, but when I was a student here we were told, don't do anything but this. So you weren't supposed to do yoga or play an instrument or write poems.

[48:41]

You were just supposed to practice Zen in the strictest sense. And I knew that there would be nothing for me if I didn't do that that I was interested in and that maybe I would write again when I came to that point and maybe I wouldn't and either was okay with me. I was willing to let whatever happened, happen. And I was very pleased when poetry came back as I began returning more to lay life after the intense part of practicing here. I had a very gradual transition back where I was living at Green Gulch, working at Green's, driving the town trip truck, but also they let me take a night off to go out to a workshop at UC Berkeley Extension and sleep in the next morning because I got home so late. And so I sort of tiptoed from Zen practice to poetry in terms of the world that I lived full time in, but I still consider myself a Zen student.

[49:42]

It's just I look more from the outside now like a poet than I do like a Zen student. I don't get to wear this very often anymore. It's kind of fun. So can I ask a question? Mm-hmm. What kind of poetry do you think you wrote before you got into Zen? Immature poetry. I was very young. I wrote love poems. I wrote a lot of love poems, a lot of sad love poems. It was interesting. There was something which I realized, I didn't look at my poems for quite a long time after I came here. I think it was maybe during my second year at Tassajara that I pulled out the collection of poems which had been my senior thesis and read them over. And I was quite shocked because I saw something I'd been completely unaware of at the time I was writing them, which was that all of my poems had endings that drifted off into

[50:45]

vapor. They had very misty endings. They just sort of dot, dot, dotted their way out of themselves. And I was appalled when I saw this because I hadn't realized how repetitious I was in my poetic strategy. And at first I was appalled because I thought, this is terrible. All I ever seemed to have wanted was to drift away into emptiness. And then I went, that's interesting. So something in me wanted to drift away into emptiness. And what did I end up doing, even not knowing that that was what I wanted? I went into a rather rigorous exploration of what do you find when you really look at emptiness. And I don't know what kind of impression you all had, but I sort of hope my poems don't dot, dot, dot their way into the mist anymore when they end. I sort of hope they end and say things. So that I remember. But I was very young.

[51:47]

I was 21 when I came to Zen Center. So it's not like I had a lot of grown-up poetry under my belt when I arrived here. And I don't know what kind of poet I would have become if I had not been here. I have no idea. How can one know? Oh. Okay. Lu and Blanche were the first two people I ever met at Zen Center. I didn't know about this place, so I went straight to Tassajara, which I knew about because a friend of mine had owned the bread book. And some early edition of the bread book had the schedule in the back of it. But fortunately, I had forgotten the schedule. All I had remembered was that there was a Zen monastery called Tassajara in California.

[52:51]

Because if I had remembered the schedule and known what time I was going to have to get up in the morning, I never would have driven down that road. But I arrived at Janesburg, and Lu and their daughter, Trudy, were living there, taking care of Janesburg at the time. And they somehow let me talk my way in. You weren't supposed to be able to go into Tassajara without practicing here first. And I knew I wouldn't do it. It's like I wanted the monastery. And I just knew if I drive away from here, it'll never happen. I'm not going to go to someplace in San Francisco. And kindness of their hearts, they took me in. They gave me Zazen instruction. I sat with them there that night, and the next morning, I got sent over the road and told to tell Blanche that Lu had said it was okay. So I'm very happy to have you here. Within this tree. Within this tree, another tree inhabits the same body. Within this stone, another stone rests.

[53:56]

It's many shades of gray the same. It's identical, surface and weight. And within my body, another body, whose history, waiting, sings. There is no other body, it sings. There is no other world. I know my poems don't leave people in the mood to ask questions. Yeah? Well, there's two things. One, of course, is day-to-day life is what you're doing here. It's not that different. This is it. You know, it's like, yes, there's a schedule, and yes, there's a community, and yes, there's

[55:00]

someone ringing a bell, but this is pretty much day-to-day life. I never felt like my years at Zen Center were ... Even Tassajara, I mean, yes, it was an incredible refuge in terms of the amount of silence and lack of distraction, but still everything was there. Ego was there. Pride was there. Irritability was there. Friendship and love and lust and all those things were there, so I never felt like you get to escape the world. What Zen practice gave me was ... And I have to be careful because the man who I live with is here, and he's going to know if I don't practice right speech. One is always aware of how we don't live up to our ideals. What I feel like it gave me was an almost continual internal request to lead my life in the knowledge of what Zen practice taught me is possible.

[56:03]

It's a very physical thing for me. It's in my body. It's like a radar that got implanted in my hara that tells me when I'm going off track, when I'm not living up to what I know is possible from what I experienced during the period that I was in this community, and a continuing flowering of what started here, because it's not like there was some pinnacle of Zen practice that from 29 I knew it all and now I'm just trying to stay there, a continuing desire to keep unfolding from that place which for me I know viscerally and without words, which is interesting. Here I am, I'm supposed to be a person of words, and yet it's quite difficult for me to talk about Zen practice because for me Zen practice exists in a realm which is not

[57:04]

particularly a language realm. It has many more axes than language does. It's much more multidimensional than language can be. Language merely attempts to point at it. But almost every morning when I wake up and I go down my driveway in the dark to get the newspaper and it's cold and it's either raining or the stars are out or the moon is out, I feel what it was like to wake up at Tassajara in the morning, that's there. And so that experience is a reminder and a request to continue practicing, even if my practice doesn't look like what it looked when I was sitting five periods of Zazen a day. I do believe that I am trying to practice in the way that I conduct my life and I can't imagine any other thing being satisfying.

[58:05]

What could be interesting? What could be satisfying once you've tasted what it feels like to try to practice? How could you possibly lead your life under any other request? Is that kind of an answer? I suppose I should talk about trying to wash dishes mindfully or something, but Michael does the dishes. I try to type mindlessly. Other questions, discussions? What was your family background? How did your family feel about you going away? I'm curious, did you expect to stay? No, I thought I was going to stay. I was going to stay for three months and learn all about this Buddhism business and then continue on my merry way and become a poet, that's what I thought. And of course, what happened was after three months all I'd found out is that you don't learn anything in three months. And so, I think by the time I'd been here three months I knew I wanted to go to Tassajara

[59:11]

and I knew I wanted to stay there for three years, which at the time was the longest anybody stayed. And I imagine that's from the traditional Asian idea of a thousand day retreat is where that came from. So I knew by then that I was seriously hooked. My family, I was raised secular Jewish, very little observation of anything, almost no communication of a spiritual tradition. I mean, there was not any sense of spirituality in our household life. We did do a Passover Seder, so there was a tiny sense of ritual. I actually remember when I was very young, and I don't know why I remember this because I've forgotten most of my childhood, but I remember when I was five or six saying to my mother, I'm so sorry we aren't Catholic because I can never be a nun. So even back then, something appealed to me in monastic life and I don't know what

[60:14]

it was. And I sort of chuckled to myself ever since, I got to be a nun. I got to wear robes, I got to follow a schedule. It's amazing to me that I got to do these things, which seemed so impossible. I grew up in New York City and I got to live in a canyon with mountain lions and a stream and no electricity and no heat. I mean, it's extraordinary that I got to do these things. They were extraordinarily gracious about it. They did not say to me, you're crazy, you're brainwashed, don't do this. I only found out after the fact when I heard that they were telling all their friends that I was doing something else while I was in California, how appalled they must have been at what their daughter was doing because they wouldn't tell anybody what she was doing. But my parents are unusual in that they don't actually lay many trips on me. It's something I'm grateful to them for, because I would have done it anyhow, but it would

[61:14]

have been just a fight. And it was sort of nice for me that it didn't have to be a fight, that they just thought I was peculiar but didn't complain to me or try to talk me out of it. I have a request, which is that maybe the next book could be titled Emotional Life of a Buddha. I think Philip Whelan or Diane could do that well. No? You don't want to do that? The next book should be called The Emotional Life of the Buddha. It's my job? Oh dear. Well, you know, this book has a lot of poems which could be called The Emotional Life of the Buddha, it's just a hidden title in there. Tricycle is going to do a special segment on it, she told me. I asked Tricycle a long time ago, I said, I want to know what other people think about this. And so she is in fact sending someone out to try to answer my question of what do other

[62:18]

people think, just so I can find out whether I'm wrong or not. I think I'll read maybe two or three, something from here, and then maybe one more poem from here, unless other people have questions that they want to ... Okay, let's see who we've got in here. One early feminist statement. You all know about the Theragatha, that the women who were allowed to join the forest community of monks with the Buddha. Theragatha, they wrote songs or sang songs about their experiences which were gathered together, the songs of the monks were gathered and the songs of the nuns were gathered. So here, right at the very beginning of Buddhism, you have women's voices telling their experience.

[63:20]

And this is the only sort of stridently feminist poem in the book, because most of the poems are supposed to be about the sacred and affirming the sacred, but I couldn't leave Sumangala Mata out. Her husband, it helps to know, made woven frond umbrellas and hats. At last free, at last I am a woman free. No more tied to the kitchen, stained amid the stained pots, no more bound to the husband who thought me less than the shade he wove with his hands. No more anger, no more hunger. I sit now in the shade of my own tree, meditating thus, I am happy, I am serene. I wrote commentaries on all of the poems. Some of them are just biographical. Some of them say, you know, sort of some of my thoughts about the issues raised by them. And I did point out that I didn't want people to get the idea that daily life is a bad thing,

[64:25]

and so I tried to correct for that, and what did I say here? It is not so much that such tasks and relationships were necessarily problems in themselves, but the attachment and distraction that they represented were. And as much as anything, Sumangala Mata's delight came from having the time and opportunity to devote herself wholly to meditation. So, you know, I kept sticking my two cents in through the book, and I hope people will be able to, you know, the women are not corrupted by my opinion, only by my taste. And people can ignore the commentaries and draw their own conclusions if they like. Here is, let's see, this is a Vietnamese woman. I knew that if there were women writing in Japan and in China, which there's a long tradition of women poets in their classical period, there had to be women writing in other Asian countries, but these women were next to impossible to find.

[65:26]

And what I was told was that it was either, you know, sort of just general sexism, which prevented their words from being kept, or in some cases, a strong influx of Confucian culture, in which case the words of the women were systematically destroyed. This is what I was told happened particularly in Korea, that the women's texts were burned. But this woman, for some reason, escaped. The poem was given to me when Arnie Kotler was going to go visit Thich Nhat Hanh in Plum Village. I asked him to ask Thich Nhat Hanh if he knew any poems by women. And he gave me a rough draft, you know, just very literal English version of this, and said, you know, feel free to turn it into poetry if you like. And then I later found it in a book in the library of women poets of Vietnam translated into French.

[66:27]

And it was a slightly different version, and that was very interesting to me, to see the version which had been collected by the French in the 1930s versus the version that Thich Nhat Hanh was giving today. So this is a very, you know, Buddhist gata-type poem. It says doctrine. But the interesting point is at the end it speaks about returning to silence. And I found everywhere, in all traditions, eventually you find women and male mystics, for that matter. It's not a women's thing, it's a mystics thing, where they say, eventually you just can't talk anymore. So there are several poems from different traditions in the book with that idea always at the end. So I don't know how to pronounce this, Ly Nhat Kieu. She lived from 1041 to 1113. And she was a Buddhist nun, the daughter of a prince, goddaughter of a king, married a

[67:32]

district chief, and when she was widowed she took vows, and she then became the abbess of a temple. Birth, old age, sickness and death. From the beginning, this is the way things have always been. Any thought of release from this life will wrap you only more tightly in its snares. The sleeping person looks for a Buddha. The troubled person turns toward meditation. But the one who knows that there's nothing to seek knows too that there's nothing to say. She keeps her mouth closed. That's the only surviving thing we have by this woman. I'll read you one Taoist woman, since it's a nice poem, speaking about the relationship between effort and realization, and how, yes, you have to make effort, but that's not what

[68:34]

realization comes from in the end. And again, I found poems all over the place that make the same statement. This is a woman named Sun Bu'er, a Chinese woman who began her Taoist practice at the age of 51 after having raised three children. She and her husband began practicing together, and they both became what's known as immortals. And she is known as one of the seven immortals, whoever they are, and she's the only woman among them. She became a renowned teacher and had many women initiates, and left not only poems for them, but also prose practice treatises. Cut brambles long enough, sprout after sprout, and the lotus will bloom of its own accord. Already waiting in the clearing, the single image of light. The day you see this, that day, you will become it. Yes.

[69:35]

Yes, I like that when people ask me to read it again. I won't impose it, but if you want to hear it, I'd love to know. Cut brambles long enough, sprout after sprout, and the lotus will bloom of its own accord. Already waiting in the clearing, the single image of light. The day you see this, that day, you will become it. I think I'll give you a second one of hers. It has a hidden cottage, that's where a Taoist hermit would be living, and it talks about apricots. And the apricots are, it actually, the same image comes up in one of my own poems that I read you, Each Step, where I talk about how the fruit is the result of the winter chill nights. I don't think I knew so explicitly when I wrote that poem, as I did after having put this anthology together, that apricot and plum blossoms, well I did because Dogen talks about

[70:38]

it, they're a traditional image for the opening of its own accord of realization, which follows the severe concentration of deep winter frost and stillness. So this poem has those apricots in it. It's also very appropriate because only we in California know that in fact it is possible for the apricot trees to begin blooming in December. People on the east coast think no, but we know they sometimes do. Late Indian summer's soft breezes fanning out, the sun shines on the hidden cottage south of the river. December, and the apricot's first flowers open. A person looks, the blossoms look back. Plain heart seeing into plain heart. Should I read you one more? Mine or the book?

[71:39]

One of each? Yeah, that's a tough question. What are you supposed to say? Hooked on the dilemma. That was Sun Bu-er, and I know I can't pronounce the Chinese. Someone can, I can't. This is a Begin, a Begin talking Buddhism. The Begins, remember, were those women, the Catholic women in the 12th through 14th centuries. I'll read you two very short poems of hers. Her name is Hattowick II, and we know nothing about her except that her poems are on the end of a manuscript by Hattowick I. But the handwriting was different, the vocabulary was different, the sensibility is different, and so she's known as Hattowick II. Tighten to nothing the circle that is the world's things. Then the naked circle can grow wide, enlarging, embracing all.

[72:42]

Now that seems to me indubitably to be a poem about concentration, about meditation. And here's another short one of hers. You who want knowledge, seek the oneness within. There you will find the clear mirror already waiting. You know, you could just... Excuse me? Yeah, this is the Begin, the laywoman Catholic. Isn't it? You know, the same image, the mirror, the dustless mirror, which is why I think that, you know, people everywhere, you know, it's all available to be seen for yourself. Most of us are a little slow and need a teacher and a teaching, but it's all available. This one's a little longer. It's called The Stone of Heaven, and as quickly becomes apparent, that's the Chinese name for jade.

[73:50]

And I'm going to have a sip of water first. And it's again about this sense of my problem with calling the sacred the sacred, when it ends up, it's just this. Here, where the rivers dredge up the very stone of heaven, we name its colors. Mutton fat jade, kingfisher jade, jade of appleskin green. And here, in the glittering hues of the Flemish masters, we sample their wine. Rest in their window's sun warmth, cross with pleasure their scrub tile floors. Everywhere the details leap like fish, bright shards of water out of water, facet cut, swift moving on the myriad bones. Any wood thrush shows it, he sings, not to fill the world, but because he is filled.

[74:54]

But the world does not fill with us, it spills and spills, whirs with owl wings, rises, sets, stuns us with planet rings, stars, a carnival tent, a fluttering of banners. O baker of yeast-scented loaves, sword dancer, seamstress, weaver of shattering glass. O whirler of winds, boat swallower, germinate seed. O seasons that sing in our ears in the shape of O. We name your colors mutton fat, kingfisher, jade. We name your colors anthracite, orca, growth tip of pine. We name them arpeggio, pond. We name them flickering helix within the cell, burning coal tunnel, blossom of salt. We name them roof flashing copper, frost-scented morning, smoke singe of pearl. From black flowering to light flowering, we name them.

[75:58]

From barest conception, the almost not thought of, to heaviest matter, we name them. From glacier-lit blue to the gold of iguana, we name them. And naming begin to see, and seeing begin to assemble the plain stones of earth. Thank you all. Thank you very much, Jane. Yes, thank you. Next month will be Karstana Hashir, who is a calligrapher, translator, poet, and so on. Thanks for coming.

[76:40]

@Text_v004

@Score_JJ