You are currently logged-out. You can log-in or create an account to see more talks, save favorites, and more. more info

Zen Directness in Everyday Life

AI Suggested Keywords:

The talk focuses on a koan related to the Soto Zen tradition, specifically from its Chinese founder, Tang Shan, also known as Cao Tung in Japanese. The discussion emphasizes the idea that inanimate objects are constantly expounding the Dharma, addressing how direct experience is fundamental in Zen practice. It underscores the importance of perceiving one's surroundings and actions without attachment or conceptualization, embodying a non-obstructed nature and compassionate interaction with all things. The talk cites significant Zen and Buddhist texts to elucidate these concepts, addressing practical aspects of maintaining this awareness in daily life and practice.

Referenced Works:

- Avantamsaka Sutra: Quotes are used to support the teaching that all lands, beings, and things expound the Dharma.

- Avalokiteshvara Sutra: Mentioned in the context of discussing other world systems and realms, reinforcing the interconnectedness and simultaneity of all experiences.

- Teaching from Dr. Konze: Discusses the different kinds of compassion—towards living beings, dharmas, and emptiness—highlighting the complexity and depth of true compassionate practice.

Key Concepts:

- Direct Experience: The core of the talk, stressing the importance of perceiving reality directly without the interference of conceptual thought.

- Compassion: Discussed in various aspects, emphasizing the need to extend compassion towards all entities and even towards emptiness itself.

- Non-Attachment: Practical advice on maintaining Zen practice amidst the distractions and demands of everyday life, such as in urban settings.

AI Suggested Title: Zen Directness in Everyday Life

AI Vision - Possible Values from Photos:

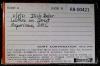

B:

Speaker: Dick Baker

Location: ZMC

Possible Title: Lecture on Direct Experience

Additional text:

@AI-Vision_v003

Well, the founder of the Soto sect in China is a man named Tang Shan, from which we get Cao Tung, or Soto sect in Japanese, and there's a koan here that he asked a teacher he visited to talk to him about, and the story is, a monk asked Hui Cheng, what is the mind of an ancient Buddha? The Hui Cheng replied, a wall and broken tiles. The monk asked, are not the wall and broken tiles inanimate objects? The master replied, they are. The monk asked, do they know how to expound the Dharma? The master replied, they are always expounding the Dharma, vigorously, without interruption.

[01:04]

The monk asked, why do I not hear it? The master replied, you do not hear it yourself, but should not hinder that which hears it. The monk asked, who can hear it? The master replied, all the saints hear it. The monk asked, does the venerable teacher hear it? The master replied, I do not hear it. The monk asked, if the teacher does not hear it, how can he know that inanimate objects expound the Dharma? The master replied, it is good that I do not hear it, because if I do, I shall rank among the saints, and you will not hear my expounding of the Dharma. The monk said, if so, living beings have no share in it. The master said, after hearing it, what will the living be like?

[02:06]

Excuse me. The master said, I expound the Dharma to living beings and not to saints. The monk said, after hearing it, what will the living be like? The master replied, they will not be living beings. The monk asked, from what sutra is quoted that inanimate objects expound the Dharma? The master replied, obviously, he who says something not in accord with the sutras is not a sage. Do you not know that the Avantamsaka Sutra says all lands expound the Dharma, all living beings expound it, and all things in the three times expound it? Thank you. Coming back to Tassajara after being away for almost continuously for three years, hearing

[03:17]

the stream makes me feel at home again. And everywhere I went during the last three years, everything in some ways appeared to me or sounded to me like the voices you hear in the stream. You listen carefully and first you think you hear something and then somebody's talking and then there's no one there. And everything I find is like that. When you examine it closely, there's nothing there. Everything has a very ephemeral nature when you examine it closely. Here at night when an airplane passes overhead, say about just after the fire watch or any time during the day, it's going very far away – I think there's one now – it's

[04:21]

going very far away to two points that we don't have any connection with, almost, that seem to have little, at least seem to have little to do with us here. Almost like it was another world, different from the time and space and pace of our life here. In that kind of experience, in a way, you've withdrawn your senses from those two points and from the airplane and all you hear is the sound. All you know of it is what you hear of it. And that's your real direct experience, the hearing of it. This is actually Buddhist practice, to find yourself in this realm of direct experience and let everything go that is not in the realm of direct experience.

[05:24]

Let your thoughts go, let your thoughts about yourself, your speculations about the past and the future, and ideas about other people. Everything should be as far away as that airplane and at the same time as near as the sound. It's actually easy to do here, and that's the great power of living here, but you also must be able to do it in the city, in San Francisco or wherever you are, if you're going to confirm your non-attached bodhisattva nature. It's hard to see it. The airplane is far away in the sky and so is your eating bowl or this lectern.

[06:27]

There's molecules and, you know, the Avalokiteshvara Sutra says there are other world systems, other realms, Buddhas on each world system, simultaneous with this one, interpenetrating with this one. In a sense, this lectern is as far away as the airplane and your eating bowl is as far away as the airplane. You have the direct experience of holding the bowl, like you have the direct experience of the airplane on your ear. Do we have the direct experience of meaning of what you say or do we have the direct experience only of the sound of it? If you have the direct experience of the sound of it, that's something. Dr. Konze, the other day, said that the miracle of a bodhisattva is that he combines emptiness

[07:40]

and compassion, and he talks about three kinds of compassion, one for living beings, one for dharmas and one for emptiness. It's fairly easy to feel compassion for living beings, since you're one of them, but harder to feel compassion for dharma and harder yet to feel compassion for emptiness. But when you treat your bowl carefully, you're having compassion for dharmas. When you're involved in thinking that you have the bowl in a different way from the airplane, then you've left the realm of direct experience, and you're involved in thinking

[08:41]

and possessing the bowl, etc. This kind of possessive thinking or ego-controlled thinking blocks your nature, and all you perceive is ego and not Buddha. Our job here is to take care of Buddha, and when we chant or work or do zazen, we're taking care of Buddha. In this way, we'll learn how to take care of the Buddha which we are. In this way, we can continue Suzuki Roshi's way, not letting our mind stray from our nature,

[10:20]

from the realm of direct experience. This is what Buddhists mean when they talk about your unobstructed nature. Suzuki Roshi, right now, feels quite good. He says his consciousness or his mind is healthy, clear, or feels quite usual. He says, it's my body only, the doctors say, is not so good. He says it doesn't matter to him whether he lives one month or one year or whatever, as long as each day he can take care of everything directly. He wants us to take care of everything directly, each day in that way.

[11:23]

And of course, that's not his way, it's our way, Dogen's way, the patriarch's way. It's a transmitted way of life which we're trying to find here. It's very, it's quite difficult to explain or to give any idea.

[12:34]

To you, what I mean sounds like a lot of words, and the talk has, such a kind of talk has no meaning unless it helps you refrain from straying from your nature. No extra words or no extra movement, no extra thoughts, nothing extra is the way to practice Buddhism until you can do it naturally under all circumstances. You can do it now by now stopping the outflows, now returning your breath to your lowest

[13:36]

Do you have any questions? Yeah. In a world of clocks and calendars, places to go and things to do, which constitute so much of our everyday life, how can we remain detached from their order? It's very difficult. That's why Buddhists in general recommend that if you're very serious about practice you don't get married, because it's one thing to have a clock always reminding you, but if you have a family and wife and a baby at once, it's very difficult. I think that's one of the things we have to find here, is how to practice in this way. But if you come to a place like Tassajara, or the city, and you understand what is meant

[15:27]

by your true nature, if you have some experience of that, then you can begin to reside there. Suzuki Yoshi used to talk about host and guest, like if there's some sunlight and there's dust in the sunlight, the dust will go out of the sunlight and come back in and move around. That's like the guest, like coming to a hotel and it comes and goes, but the sunlight, the light remains the same. So if you have some sense of that light in yourself, then the clocks or the activity or whatever you do, it comes and goes freely, like the guest.

[16:28]

But if you go with the guest, then there's no host at home, then it's difficult. So when we practice here, we're trying to return to our true nature. Yeah? You made great emphasis on direct experience, and yet it is written that it is great power to uncover one thing and uncover three. How do you reconcile that? To know one, to know three by knowing one corner, is the saying, I guess, or they sometimes count eight corners, just means that you should know something thoroughly by seeing

[17:32]

only one part of it. If you hold something up, if you only see a corner of it, you should know what the whole is by seeing only a part. Can you give us an example of something that's not direct experience? Well, in talking about the airplane, if you are wondering where the airplane is going or what the pilot's doing or that kind of thing, that's not direct experience. Can you directly experience the wondering? The what? The wondering. Is that not in the realm of direct experience? Well, it's not what I mean by direct experience. It's a kind of experience, it's true. If you have your eating bowls there and you're concerned with how good they are or what color

[18:36]

they are or whether you should be using them or something like that, that's not your direct experience in a sense. But you can become aware of the fact that you're wondering about that, and is that not also direct experience? Yeah, to be aware of that wondering is certainly direct experience. That's the only way you can free yourself from that kind of trained thinking, is to be aware that you're doing it. And then, even though it goes on, you can still directly experience it? Well, it depends what you mean by direct experience. But anyway, that's not direct, it's just... What I'm asking, Dick, is as that wondering is going on and you're aware that that wondering is going on, is that what you mean by direct experience? Now, direct experience is you're holding the bowl, or you're hearing the airplane, just

[19:38]

you're hearing the airplane, that's all. No, you don't have to have any thoughts about what it is or anything, unless you're going to want to take the airplane next time you go from San Francisco to Los Angeles. Like in Zazen, when you really only know you're breathing, that's your real direct experience. If some thought arises, of course, that's just the activity of the mind. But then, if you get your identity mixed up with those thoughts, and thinking about it, and what it means, etc., that's... you're no longer in the realm of direct experience. I thought of... there are six ways to... how to give help to yourself.

[20:45]

One is how to help... how to give help to yourself through nothing at all, emptiness. And one is... two is how to give help to yourself through all things. That would be like the eating bowl or whatever. And how to give help to yourself through yourself. And how to give help to yourself through your teacher, and through your friend, and through the sangha. And the way to do that is to be... is to be compassionate with emptiness, or with all things, or with your teacher, or with yourself. You have to make... your teacher doesn't give you help so much as you find out how to make your teacher help you.

[21:55]

And your friend, who you practice with, and the sangha as a whole. And the way to do that is to be compassionate with everything. And that... the way to keep the channels open between people is with courtesy and consideration. Even if you're angry with courtesy and consideration, channels stay open between each person and everything. Question from the audience. Question from the audience. What kind of feelings? Yes. Yeah, that obstructs you, blocks you.

[23:01]

Yeah, well... In a sense of attachment, yeah. It's impossible not to have some special feeling for other people. But as Dan said, you know, you can be aware of that, and the awareness of that gives you a freedom from it. But if you have special feelings for all kinds of things, if you worry about, the city's better than this, and that's better than that, then you're really caught. Yeah, what I'm... what I'm trying to do a little bit, it's kind of... maybe too complicated, is Buddhism uses all kinds of terms like host and guest and non-obstructed and non-abiding, to use your word,

[24:09]

to not abide anyway, to have a... the term non-abiding is used a lot. And in a way this is a special vocabulary that allows you to talk about or hint about what can't be talked about, which is what the Shuso ceremony's about. Because you can't talk about your true nature, and you shouldn't talk about it, and if somebody asks you about it, there's nothing to say about it. But maybe it's... maybe it's... you know, I have a... Suzuki Roshi, when he first came to America, talked about this kind of thing at some length, but then he stopped talking about it. Maybe it's too difficult, or it doesn't make sense to us, you know. I don't know. But I listened the other day to us talking about how to eat and how to handle the bowls,

[25:15]

and then the preparation for the Shuso ceremony, and I wondered if we could come to... if it would be worth talking about some of these terms and get an idea of what they mean. They're through all the Zen stories, and most people read them, they don't know really what is meant. Could you give an example of that? Of what? I sort of lost you there. An example of these terms, by a term... Well, just in that story I read you right in the beginning. Which term? Non-obstructedness. He talked about Buddha being on the inanimate objects preaching the Dharma. What does it mean, inanimate objects preaching the Dharma?

[26:15]

What does it mean to have compassion for Dharmas, or compassion for emptiness? Or how can you... if we say everything is empty, you know, has no self-nature, no own being, how can you be compassionate for something that's empty? It's no more difficult than being compassionate to sentient beings. It's no more difficult? That's true, it's no more difficult. But that's how you take care of the bowl, that's how you take care of everything. Doesn't answers reply in direct experience? I mean, before there's deep experience, there's no contact with meanings. Deep, you say? Before there's direct experience. Before you directly experience compassion, emptiness, airplanes, noises, then...

[27:18]

Well, I wouldn't... All right, before you... Airplanes and compassion. All right, before you directly experience, then, even if you've studied a term in great length, what's the connection between the term and the experience? Encouragement? Well, with compassion, I think, it's not something you can talk about so much, but if you practice courtesy and consideration for everything, then compassion will be there. Yeah. I can understand compassion arising out of emptiness,

[28:19]

but what's compassion directed towards emptiness? Well, if you have compassion for things, you have compassion for emptiness, or compassion for anything, you have compassion for emptiness. But whatever that means... I'm sorry, I said... Yeah. I was wondering about the way you were using direct experience, if you meant, by direct experience, grasping of something with the senses. Yeah. I mean the practice of nothing extra.

[29:20]

Nothing extra, then what? Um... Just what's necessary. Yeah. What makes you think there's anything extra? Do you find anything extra in your life? Not right this moment. Did you before you came here? I think at various points I've had that idea. I think that idea itself, though, may be the obstacle. That's true. I'm sorry I talked about something so complicated.

[30:38]

Thank you very much. You're welcome.

[30:50]

@Transcribed_v002L

@Text_v005

@Score_92.89