You are currently logged-out. You can log-in or create an account to see more talks, save favorites, and more. more info

Sunday Lecture

AI Suggested Keywords:

The talk delves into mindfulness practices, drawing from early Buddhist teachings that emphasize knowing, shaping, and freeing the mind. The practice of 'bare attention' is highlighted as a core component for cultivating mindfulness, with the speaker emphasizing its role in eliminating distractions, self-referencing, and judgment, aiding in a deeper presence and attention to daily life. The discussion includes reflections on how mindfulness ties into broader principles like compassion, loving-kindness, and nonviolence while emphasizing the importance of personal effort and responsibility in spiritual growth.

- Dhammapada: A classical Buddhist text that emphasizes self-reliance and personal effort in the pursuit of purity and mindfulness. It is referenced to highlight the necessity of personal engagement and responsibility in one's spiritual practice.

- Mindfulness Practices: The talk relates these to early Buddhist teachings as essential for shaping the mind and achieving liberation, underscoring their critical role as a 'master key' in understanding and transforming mental states.

- Bare Attention: This practice is described as central to the mindfulness tradition, focusing on observing thoughts and sensations without judgment or additional mental commentary.

- Practice of Zazen: Identified as a core method within the mindfulness tradition for cultivating presence and insightful awareness through sitting meditation, emphasizing posture and breath awareness.

- Cultivation of Compassion and Loving-kindness: Discussed as fundamental aspects of the mindfulness approach, guiding practitioners to embrace nonviolence and understanding towards oneself and others.

AI Suggested Title: Bare Attention: Mindfulness Unlocked

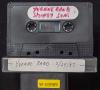

Speaker: Yvonne Rand

Possible Title: Sun.

Additional text:

@AI-Vision_v003

Recording starts after beginning of talk.

It's kind of nice having the bridge up. Just before I came into the Zendo, I said to someone, wouldn't it be nice if we had a Dharma drawbridge? And then when it gets to be a little too full, we can just pull it up. Anyway, it's nice to be a somewhat smaller group of us together. As some of you may know, there is a group of us together this weekend practicing so-called mindfulness practices, those practices that are conducive to cultivating our ability to be awake and present in each moment.

[01:07]

And what I'd like to talk about this morning is a particular aspect of mindfulness practices. And if possible, to suggest some examples of how some practices may work in terms of the sort of practical nuts and bolts of it. But to also make some however brief of the surround or context for cultivating such capacity or capacities. In the early teachings of the Buddha, the Buddha talks about there being three things having to do with the mind. One is to know the mind, which for many of us, anyway, has some quality of being very near and also in some way unknown.

[02:18]

The second thing is to shape the mind, which is sometimes unwieldy and stubborn. and also has great capacity for pliancy and flexibility. And the third is to free the mind. Sometimes we have some experience of a kind of bondage which we have held by the mind, a kind of vice or grip. And yet the Buddha is saying it is possible to cultivate some capacity such that we have a kind of freedom or liberation right now. In these early teachings, the mindfulness practices, the cultivation of mindfulness is described as useful because it's a kind of master key

[03:34]

in this work of knowing the mind. It is extremely critical aspect of the work of shaping the mind. And it is at the same time the manifestation of liberation. So when we talk about mindfulness, what are we talking about? We're talking about paying attention, taking notice of what is around us and within us in each moment. And in this great tradition of mindfulness, We want to practice as much as we can carefulness and a kind of rigorous, comprehensive investigation of matters as they arise.

[04:39]

In the texts on mindfulness, the description of what mindfulness leads to is pretty inviting, I think. greater clarity, intensity of consciousness, a picture of actuality with an increase of purging of any falsifications. Interesting descriptions. The particular detail of practice that I would like to bring up this morning is the practice of bare attention, which is described as clear and single-minded awareness of what is actually happening to us and in us in successive moments of perception. That is, without anything extra added.

[05:53]

What are the extras that we might add? Some reactiveness, either in our activity or in our speech or in our thoughts. Mental comment. In particular, what may come up and seems to come up over and over again for many of us is kind of self-referencing or kind of preoccupation and worrying about ourselves. Judgment. That particular kind of judgment that has to do with a little inner voice, running commentary. How am I doing? How does it compare to what I did the last time or what my neighbor is doing? Sometimes that voice may take the form of a kind of editor. Lots of commentary about what I like or dislike.

[07:00]

Kind of reviewing and reflection of things that have happened. But in this business of bare noting or noticing, bare attention, when these kinds of thoughts or responses arise, one of the possibilities is that we can then let that material, that response, that particular thought become the object of our attention. We can notice all those thoughts, the judging voice, pay attention as accurately and carefully as we are able to, and then dismiss whatever it is. And that's where many of us get stuck. We have some habit often of hanging on to whatever those responses are.

[08:09]

And in fact, for many of us in this area of our practice, it is as if we've dug a kind of deep groove. And the needle, the phonograph needle, is staying stuck in that particular groove, doesn't so easily move to the next groove called dismissing the judging thought, for example. Because the ridges, there's too much of a jump there. It takes a kind of effort of attention and energy The ground on which we practice in this way is a ground which includes also the cultivation of compassion and of loving kindness, a ground which includes our attention to our intention to live our lives carefully and with some

[09:16]

effort with respect to our conduct, a life which is based on patience and nonviolence and loving kindness. So we want to keep that always as the field, along with our cultivating mindfulness and concentration and in the particular circumstance of practicing bare noting. One of my experiences, both for myself and with other people, is that beginning to be more awake to that inner voice, that judging, whatever is extra to the bare attention, is a time when sometimes what arises is some very critical judging attitude towards ourself, and that it is exactly at that point that our ability to include ourselves as the objects of loving kindness and compassion, along with

[10:38]

such attitude towards others is quite crucial and often very difficult. But I think they do go hand in hand. As I was sitting a little while ago before it was time to come to the Zendo, sitting quietly, Letting my attention follow my breath. And then somewhere in the midst of the inhalation, some thought arises. Did I turn off the water before I left the house? Back to my grandma. I should remember to call my mother. Excellent.

[11:41]

What herbs do I want to plant in the garden tomorrow? Go back to the breath. And then some thought came up, I guess tagging on the herbs in the garden. some thought about this precept that I've been struggling with for the last year about not killing, which comes up for me so exquisitely whenever I meet the snails in the garden. And I was thinking about what I wanted to say this morning in terms of the field, including a life devoted to nonviolence. And, of course, very quickly the snails come up for me. because I'm torn about jumping on them, hurling them vigorously as far into the distance as I can. And so these thoughts begin to have a life of their own.

[12:56]

And at some point, I notice thinking, snail, violence. How does this relate to the precept that I'm working with? At that moment, noticing that detail, that sequence of thoughts, and then returning to my breath again. Am I willing to allow myself that moment of touching, noticing those thoughts, but to not stay there, not get enticed into some little inner discussion with myself about, well, from some larger ecological point of view, if I kill the snails and that helps the plants grow. And pretty soon I had this whole conversation that draws me away from my intention to practice sitting quietly,

[14:00]

letting my attention be with my breath, noticing as carefully as I can, in particular detail, the movement of the breath as I breathe in and out. And as these thoughts arise, noticing them also, and then just allowing them to go, dismissing them, but with some delicate, friendly quality, not pushing or getting caught by some discussion with myself about how I'm doing in this moment of practicing zazen. Right in that region seems to be one of the places that for many of us we get caught. Or as I'm sitting quietly, I notice some, like a low murmur, a feeling, a little unsettled.

[15:09]

I can let my attentions settle with that experience or feeling or whatever the words are that come to describe what I'm in touch with. But am I willing to, at some point, fairly quickly return to my breath and trust that whatever I'm beginning to touch and noticing some quality of unsettledness will begin to be more clear to me? If I'm willing to hang out in this way, gently, always coming back to my breath, to my posture. And what I notice is that I very easily get caught up into an inner dialogue about particularly something like an arising quality of unsettledness, what's going on, worrying it.

[16:18]

Instead of just allowing whatever is there to be there, much the way the breath is, arising but also falling away. I was looking at a text called the Dhammapada earlier, and there was one line in the text that really caught my eye in terms of what we are doing together exploring these various practices for cultivating mindfulness. Because, of course, what comes up is what are our reference points? Who do we depend on? Do we have a teacher or a guide? Do we have some friends on the path who will help us? Is there someone who will show me what this looks like? Some people who will be examples of what we're talking about?

[17:26]

All of that referencing to other. And I enjoyed seeing this particular line which goes, Pure and impure on self alone depend. No one can make another pure. The effort you yourself must make. That kind of reminder that we can read about practices, but the proof of the pudding is in whether we actually do them. As a monk who visited us recently said, It all depends on the purity of our intention. And of course, that is up to each of us in each moment. And there are times when my intention is on the purity scale, maybe a little more where I'd like it to be. And there are other times when it

[18:28]

shift down into this gray or murky zone, which is a little more problematic. But as long as I remember that it is ultimately up to me to accept, embrace responsibility for what I'm doing as clearly as I can. In the context of being helped by my friends and teachers, I don't look outside for that which only I can do. One of the practices that we've talked about, and some of you have heard me talk about in lecture before, is the practice of a half-smile. And I was thinking last night just before I went to sleep about that wonderful expression which is depicted on so many drawings and figures, carvings and all Buddha figures, how they seem to have often in common this wonderful smile.

[19:46]

the smile of the Buddha, and how much that smiling is a kind of reminder for me, and I think for many of us, a kind of assurance, that smiling which I hope will remind all of us that what the Buddha talks about in the teachings is completely attainable by each of us. And some assurance, some encouragement that that's possible. In the Buddhist tradition there is an emphasis on cultivating mindfulness, self-reliance, all these various capacities, but with some understanding that we cultivate these qualities very gradually, and that if we are energetic and persevering and patient, kindly,

[21:03]

We can, in fact, change ourselves, change our lives in ways that lead us to be a little bit closer to our intention, our yearning to be clear and present and open-hearted. Often we have habits, we have certain tendencies, depending on other people, all kinds of habits. And it seems to me that part of what happens when we go into our automatic patterns, whatever they may be, in our activity or in our speaking, in our thinking, Even in our emotional and psychological life, we may begin to notice certain patterns. That in those habitual patterns, those are the places in our lives, those are the moments in our lives when we tend to be the most asleep or not conscious, not attentive to what's actually going on.

[22:17]

So all of the various practices in the mindfulness tradition, in a very radical but subtle way, the practice of zazen, of cross-legged sitting meditation, which is the heart of our practice here, these are all efforts to wake up in those moments of our lives when we tend to be asleep. And if we can be patient with ourselves, particularly if we're willing to set aside some time, ideally every day, when we are willing to sit down quietly and pay attention to our posture and our breath, that we may gradually, in an unfolding way, cultivate our ability to be more awake and more present in each moment. that we can start by practicing being with ourselves in that way for even a few moments every day.

[23:27]

If what we want to do is to develop our ability to pay attention, where do we begin? What are we going to pay attention to? We can begin by paying attention to all of the tiny details of our daily life, most ordinary, everyday events, whatever is happening to us at each moment. We don't have to go to someplace special to do that. We can begin immediately in the life we actually have. And so, of course, what happens then is that the details of our daily lives become our teachers. Those details then become the source for our penetrating clearly some deep understanding, some real wisdom as to how things actually are.

[24:42]

I think it is extremely useful, probably for most of us really necessary, to have some place that we can go to where we can be still, where we can be quiet. Some place which is committed to a life which is a little bit more simple than the life most of us are able to lead every day. to have periodically some time of refreshment that arises out of simplicity and quiet. Hopefully, a place like Green Gulch can provide such a resource, a place which is conducive to quiet and simplicity. But I would encourage all of us, myself included, to remember that we can also pick up, be present with the detail of our daily life and say, oh, you 50,000 snails in my garden are my teacher.

[26:06]

The telephone witch. suddenly isn't working. And in that moment of frustration because I want to make some phone calls and what arises, there is a possibility for me to learn something in that moment. Driving the car over the hill behind one of the tour buses. a great opportunity for cultivating patience, for noticing some inclination to get somewhere, do we even know where, to notice our habit for rushing, to have all kinds of comment about the bus or the bus driver, what arises when we're halfway to San Francisco and realize we actually are supposed to be going to San Rafael.

[27:20]

And in these moments, these details of our daily lives, which we can relate to as an opportunity to be taught about what's actually going on, we have the possibility of noticing in as much detail, descriptive, careful, thoroughgoing detail, what's happening, what's happening around me and what's happening within me. But to also remember that we can dismiss it, allow it to go. We do not need to worry the details to death. And my experience of practicing in this way with the very most ordinary details of daily life is that what arises, among other things, is some quality of joyfulness and real calmness.

[28:38]

Gee, where did that come from? I don't have so much difficulty being friendly to those kinds of things arising. I find it a little bit more troublesome, though, when some voice arises which is cranky or where I notice that I'm feeling irritated or some quality of intense negative emotion towards some situation or towards a particular person. That's where I find the practice of bare noting or bare attention more difficult. In the attention so quickly comes all that other additional commentary.

[29:41]

So what I can do is to keep returning to my effort to be as descriptive as possible and then let it go. If there's more to be examined here, I can trust that it will arise again. For those of you who have not been here before or who are not familiar with Zen sitting meditation, At some level, it seems rather simple. We put some emphasis on sitting with our legs crossed if possible, but particularly sitting in some posture so that we can have our back straight in some stable, open, relaxed posture. And in addition to attending to our posture, letting our attention settle with our breathing, just following the breath, not controlling the breath, noticing the breath as it arises and falls away, roping the mind.

[31:05]

so that instead of having a succession of many thoughts with the top ten tunes, whatever is playing on your radio this morning, you can rope that busy mind, that tendency to worry and fuss over one thing and another, to the detail of physical posture and breath. And in the context of that practice, pay attention, bear attention to the detail of posture, breath, and when the thoughts arise to those thoughts or when some strong physical sensation or feeling arises, to notice that and then allow it to go. So in our exploration this weekend of mindfulness practices, in everything we've picked up and looked at and tried, there's always this practice called their attention.

[32:21]

Sometimes gets to be more particularly notice the judging, editing voice and let that go. Let that become the object of attention and let it go. always with some kindly, friendly, open-hearted attitude and feeling. So in the next little while, when you're here at Green Gulch, having a cup of tea, or as we discuss whatever comes up in the discussion, as you're eating lunch or going for a walk in the garden. Please, for a few minutes, allow yourself to notice as thoroughly as you can the detail of one or two or three moments in succession with as much attention as you can.

[33:33]

And consider the possibility of doing that for a few minutes every day. You might be surprised at what happens. Some of these practices sound so simple. But my experience anyway is that they may be simple, and they also are challenging. I find myself feeling challenged. And I am continually amazed at the subtleness and possibility for going deeply, always more deeply, into my life and what happens out of the ground that is cultivated by doing practices like the ones I've been suggesting. I think we've all had those experiences when we've had a meeting with another person or have been somewhere.

[34:44]

Often it happens when we go on a vacation, when we go to the high mountains, and we sit down in some very beautiful spot, and for a moment we don't have any thinking that takes us away to the present, to the past, or to the future. We're simply in that moment. thoroughly and completely in touch with the interconnectedness of all things. And we enjoy a kind of settledness and calmness and joy. But I think for some of us we think that this kind of experience may fall on us like rain. In some religious traditions, there is some talk of grace, being in a state of grace, variations on that description. We stumble into those moments. But we can also cultivate our capacity for being present in that way.

[35:53]

In a funny way, not so different from the way we learn to ride a bicycle or to drive a car or to play the piano. We set aside a particular time when we will practice certain skills that bring together our capacity to ride on this two-wheeled, object with this funny seat in the middle of it in a way that allows us to go all the way to the beach without falling over. We can cultivate our ability to be present and awake. It's actually a fairly radical intention. Because, of course, it means and includes our willingness to be awake to everything, no editing.

[36:56]

And most of us think, well, I'm willing to be awake and present for the nice things, the pleasant things, but I don't know about the things that are dark or demonic or upsetting or ugly or painful. And of course, immediately we're caught. We're in that realm of suffering because there we are, avoiding some things and yearning for others. And inevitably, the things we hope will go away, even if they go away, they arise again. And the things that we enjoy and we want to hold on to slip away. constantly changing. The people that I've met who have been deeply trained and practiced and experienced in this tradition, the mindfulness tradition, the tradition of cultivating this kind of big awakeness,

[38:13]

have consistently been people that I have felt inspired by, that I've enjoyed being around. I think that such people are extremely important and necessary in our lives. And we do recognize them when we see them. People who have some quality about them of harmony, of calmness, of joyfulness. And most of all, some quality which leaves me feeling like I've been seen and heard and understood with some assurance or affection, some loving kindness quality, which is quite palpable. And what I hope for myself and for all of us is that we can all cultivate our capacity, our deep capacity, each of us, to be such people.

[39:21]

Certainly, we all know that we can be in this way for ourselves and each other occasionally. So I hope we can together support each other in having more of those occasions. Thank you very much.

[39:48]

@Transcribed_UNK

@Text_v005

@Score_94.31